In this article, the terms NAFS and NAFS-08 refer to AAMA/WDMA/CSA 101/I.S.2/A440-08, NAFS—North American Fenestration Standard/Specification for windows, doors and skylights.

NAFS Changes Everything

NAFS, as implemented in Canadian building codes, changes everything—not only for Canadian manufacturers, builders, code officials and architects, but also for American manufacturers who may not realize that NAFS in Canada is very different from NAFS in the U.S. (I invite U.S. readers of this blog to read through to the end of this article. Your existing NAFS test reports may not contain enough test data to qualify your products to meet Canadian code requirements.)

NAFS changes everything about window and door selection and product testing in Canada, and it’s fair to say that there is currently a great deal of confusion and misunderstanding about how NAFS is to be applied to Part 3 (“Commercial”) and Part 9 (“Residential”) buildings in Canada.

If you sell or specify windows and doors in Canada today, you need to know how NAFS is applied under Canadian building codes. This blog will help you.

NAFS—the “Harmonized” Standard

Known officially as AAMA/WDMA/CSA 101/I.S.2/A440-08, NAFS—North American Fenestration Standard/Specification for windows, doors and skylights, we call it NAFS-08 in Canada because NAFS-11 is not currently recognized by Canadian codes.

Known as the Harmonized Standard in the Building Code, the NAFS standard represents a monumental attempt to harmonize Canadian and American testing and performance rating regimes, tracing its roots back to three older standards that predated it:

| Country | Standard | Issuing Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | CSA A440 | CSA Canadian Standards Association |

| USA | AAMA 101 | AAMA American Architectural Manufacturers Association |

| USA | WDMA 1.S.2 | WDMA Window and Door Manufacturers Association (formerly and National Wood Window and Door Association) |

The first NAFS standard recognized by all three issuing organizations was issued in 2008, and the second is dated 2011. It’s the 2008 version of NAFS that is referenced in Canadian building codes.

Where is NAFS Compliance Required in Canada?

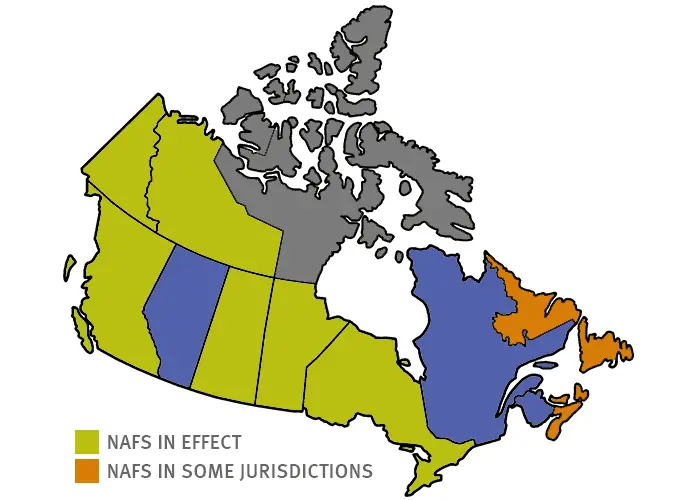

NAFS made its Canadian debut in the 2010 National Building Code of Canada (NBC), and currently applies to buildings in most of the country.

Construction is provincially regulated in Canada. Several provinces (and a few cities) have their own building codes based on the NBC model code, but most provinces and territories eventually adopt the NBC, often with amendments. The NBC applies to buildings under federal jurisdiction in Canada, such as military bases, federal government land, first nation reserves and airports.

The following provincial codes currently require NAFS compliance:

- 2012 B.C. Building Code

- 2012 Ontario Building Code

- 2014 Vancouver Building Bylaw

As of August 14 2014, the NAFS standard is in effect in all provinces except:

- Alberta,

- Quebec, and

- New Brunswick (except the city of Moncton, where it is in effect)

For a detailed list of jurisdictions and the dates on which NAFS requirements apply, see Building Code Rumours.

4 Things Everyone Needs to Know About NAFS in Canada

1. Location-specific Performance Requirements

Canadian building codes explicitly require fenestration products to have performance ratings specific to each building’s location, height, and terrain. This has huge implications for all parties involved in the specification and supply chain, as alert building officials will be studying labels to ensure the Performance Grade and Water Test Pressure values are appropriate for buildings in their jurisdiction.

Here’s how the Building Code puts it:

“Performance grades for windows, doors and skylights shall be selected according to the Canadian Supplement [CSA A440S1-09] . . . so as to be appropriate for the conditions and geographic location in which the window, door or skylight will be installed.”

See NBC 5.10.2.2.(2) and 9.7.4.3.(1)

The Canadian Supplement CSA A440S1-09 provides simplified methods for determining the Design Wind Pressure and Driving Rain Wind Pressure for buildings anywhere in Canada, situated on level ground. The Design Wind Pressure determines the required Performance Grade, and the Driving Rain Wind Pressure determines the required level of water penetration resistance, which in coastal areas can be much higher than 15% of Design Pressure, which is how water penetration resistance is rated in the U.S.

What does this mean for U.S. manufacturers? It means many U.S. products will not have sufficient water penetration resistance to meet code requirements in coastal areas of Canada.

2. No More ABC Ratings

NAFS overwhelms Canadian manufacturers, architects, and code officials with new concepts, new terminology, and a new rating system. We need to learn a new language to be able to talk about these things!

NAFS introduces a brand-new performance attribute called Performance Class. And instead of the familiar ABC ratings, we now talk about Performance Grade, Water Penetration Resistance Test Pressure, and Canadian Air Infiltration/Exfiltration Levels.

| The New: NAFS-08 | The Old: CSA A440-00 |

|---|---|

| Performance Class: R, LC, CW, and AW | |

| Performance Grade: PG15 – PG100 (in 18 steps) | |

| Air infiltration/exfiltration: A2, A3 or Fixed | Air infiltration/exfiltration: A1, A2, A3 or Fixed |

| Water penetration resistance: 140 – 730 Pa (in 18 steps) | Water penetration resistance: B1 – B7 |

| Design pressure: 720 – 4800 Pa (in 18 steps) | Wind load resistance: C1 – C5 |

| Applies to most window, door and skylight products | Applied to windows only |

3. A Lot More Lab Testing

Existing test reports from earlier standards (NAFS-05, CSA A440-00) do not contain the necessary data to determine NAFS-08 ratings, and therefore all manufacturers must specifically test their product lines to NAFS-08 to comply with Canadian codes. NAFS testing requirements for products with mullions are also much clearer and more explicit than in earlier Canadian standards, and as a result window manufacturers need to do far more product testing than they have been accustomed to in the past. On top of that NAFS covers products that previously were not subject to testing: unit skylights, tubular daylighting devices, and side hinged doors.

4. Side Hinged Doors Included

Did I mention side hinged doors? Canadian codes require exterior side hinged doors to be NAFS tested, and unprotected doors must have the same air-water-structural performance ratings as windows.

And NAFS testing reveals an uncomfortable fact: the doors we’ve building and buying for many years did not meet the performance levels the Code expected of the windows installed beside them.

This is a particular challenge to American door manufacturers, as in the U.S. side hinged doors do not need to comply with NAFS-08.

Harmonization: Dream vs. Reality

The hope was that Canadian and American manufacturers could test once, and have the ratings recognized in both countries.

This proved more difficult than anyone could have imagined. CSA negotiators did not want to reduce existing CSA performance requirements, or the ability to rate air, water and structural performance independently of one another.

On the other hand, American negotiators did not want to add to the performance testing requirements that had been in place in the US for decades. As a result, there are separate Canadian and American tables in NAFS for optional performance grades, operating force, force to latch, and air tightness (air infiltration-exfiltration in Canada).

And that’s not all: there are additional Canadian-only performance and labeling requirements in a companion document, CSA A440S1-09, the Canadian Supplement to NAFS-08.

| Supplementary Canadian Qualification Requirements | |

|---|---|

| CSA A440S1-09, the Canadian Supplement to NAFS-08, requires the following requirements to be met in addition to those in NAFS-08: | |

|

|

What Harmonization Means for U.S. Manufacturers

They need to know that products tested and certified to the American requirements in NAFS do not automatically comply with Canadian codes. To comply with NAFS in Canada, as referenced by Canadian building codes, they must also be tested to the “optional” Canadian requirements in NAFS-08 as well as to those in the Canadian Supplement, and be correctly labeled to show their performance using both Primary and Secondary Designators.

Sound confusing? To address this, the Fenestration Canada organization has published two labeling guideline documents to assist manufacturers, building officials, and certification organizations:

- The NAFS Labeling Guidelines for Canada address the content of labels and illustrate the variety of formats used in the industry

- The Voluntary NAFS Labeling Guidelines for Products with Mullions provide additional guidance on the testing, rating and labeling of mullion assemblies

A third Fenestration Canada document provides guidance to fenestration manufacturers and their engineers on the use of engineering calculations in conjunction with testing: Recommendation on the Use of Engineering Calculations to Determine Design Pressure Ratings of Fenestration Products under NAFS-08. This document will be of interest to users of NAFS-11 as well.

These are must-read documents for Canadian manufacturers too.

What Harmonization Means for Canadian Manufacturers

Since Canadian NAFS testing requirements are more stringent than those in the U.S., properly conducted Canadian test reports should contain the information necessary to qualify them for use in the U.S. (More on the difference between Canadian and U.S. NAFS testing below.)

What U.S. Manufacturers Need to Know about NAFS in Canada

Many U.S.-based fenestration manufacturers will find that their NAFS test reports do not contain enough test data to qualify their products for the Canadian market, or to label them using Primary and Secondary Designators. I have spoken with several U.S. manufacturers who were disappointed to find themselves in this situation. After all the harmonization efforts, why is that? Perhaps they assumed that NAFS is NAFS, on both sides of the border. Well, it’s not. Or that the Canadian test requirements in NAFS were optional. Well, they’re not optional for products destined for the Canadian market.

If a U.S. manufacturer’s existing test reports do not have test data to demonstrate compliance with the Canadian requirements in NAFS-08, the product Primary Designators may not be valid, and the reports will not contain the information needed to report the Secondary Designator ratings which are optional in the U.S., but mandatory for NAFS labeling in Canada.

Then there is the question of products tested to other versions of NAFS. Canadian building codes refer only to the 2008 version of the NAFS standard. While it is possible that some code jurisdictions will accept NAFS-11 test ratings at some point in time, they will not accept ratings based on NAFS-05.

Canadian operating force requirements

Products sold in Canada are required to be easier to operate than in the U.S.

Table 6 of NAFS-08 presents the Canadian operating force requirements, and they are significantly different than those in Table 7 for the U.S.

Table 6 specifies a maximum force to initiate motion, while Table 7 does not. And for all products, the maximum force to maintain motion is lower in Table 6 than in Table 7. How does this affect performance ratings in the Primary Designator?

It means U.S. NAFS ratings for products that have higher operating forces than shown in Table 6 are not valid in Canada. The operating force test is performed before air and water testing of products, and the tested air and water penetration ratings depend on the weatherstrips and hardware used for the test.

Take the case of a sliding sash product, for example. It may achieve higher air and water ratings tested under Table 7 for the U.S. market, and lower air and water ratings for Canada if thinner weatherstrips are required to meet the Canadian operating force requirements. And lower air and water ratings can result in a lower overall Performance Grade.

If a U.S. product requires use of different weatherstrips or hardware to comply with Canadian operating force requirements, its U.S. ratings are not valid for Canada, and must be retested using components that do meet Canadian operating force requirements.

Canadian air leakage ratings

There are three significant differences between Canadian and U.S. air leakage measurement in NAFS.

- In the U.S., air leakage has always been measured in one direction: into the building under positive pressure. In Canada, air leakage measured in both directions, into and out from windows, for the logical reason that windows are subject to both positive and negative wind pressures, and windows often perform differently under positive pressure than under negative pressure. NAFS-08 Table 8 presents the U.S. maximum air leakage rates. Table 9 presents Canadian air infiltration/exfiltration leakage rates and ratings.

- With the exception of the AW Class, the maximum air leakage rate for U.S. products is the same for fixed and operable products. This is not the case for Canada. Table 9 has two levels of Canadian air infiltration/exfiltration for operable products, while the rates for fixed products.

- The allowable rates of air infiltration/exfiltration in Table 9 are much lower for all products, including AW Class products, than they are in Table 8.

Canadian water penetration resistance ratings

In Canada, water penetration resistance is specified separately from Performance Grade, and is reported in the Secondary Designator on product labels. In much of the country, especially in coastal areas, it needs to be significantly greater than 15% of design pressure (20% in the case of AW products). And in Canada, water test pressures are tested all the way up to 730 Pa (15 psf), and are not capped at 580 Pa (12 psf) as in the U.S.

American test habits

Because the water penetration resistance test pressure is tied to the Performance Grade in the U.S., there is little incentive for American manufacturers to test this property beyond the minimum.

For example, an R, LC or CW Class product with a Performance Grade of 40 is tested to a minimum water penetration resistance pressure of 290 Pa (6.0 psf). If the product could achieve a higher water test pressure, say 440 Pa (9.0 psf) or 730 Pa (15.0 psf), there is no way to report this benefit in the Primary Designator.

The unintended consequence is that many U.S. manufacturers do not test water penetration resistance beyond the minimum value, and in my experience, U.S. test labs typically stop testing water penetration once the minimum value is achieved.

As a result, many U.S. manufacturers will find they do not have products rated for the water penetration requirements in Canadian coastal markets where water penetration resistance levels greater than 15% or 20% of design pressure are required.

Don’t forget the Canadian Supplement

So far we’ve looked at the differences between Canadian and U.S. testing requirements within NAFS. Canadian Codes require products to also conform to CSA A440S1-09, the Canadian Supplement to NAFS-08 which contains additional test requirements.

If you’re an American manufacturer with eyes on the Canadian market, you need to bring up one more subject when you chat with your U.S. test lab: additional tests (such as the insect screen test) and component requirements, and one very significant difference: the definition of water penetration resistance in the Canadian Supplement.

Yes, NAFS Changes Everything

We have landed in a new Code world. Whether you are in Canada or in the United States . . . if you manufacture, specify or sell windows and doors for the Canadian market—NAFS in Canada changes everything.

Stay tuned for more in-depth blog posts on topics related to the NAFS standard and Canadian fenestration issues, and feel free to comment below or ask questions.

Note: In this article, the terms NAFS and NAFS-08 refer to AAMA/WDMA/CSA 101/I.S.2/A440-08, NAFS—North American Fenestration Standard/Specification for windows, doors and skylights.